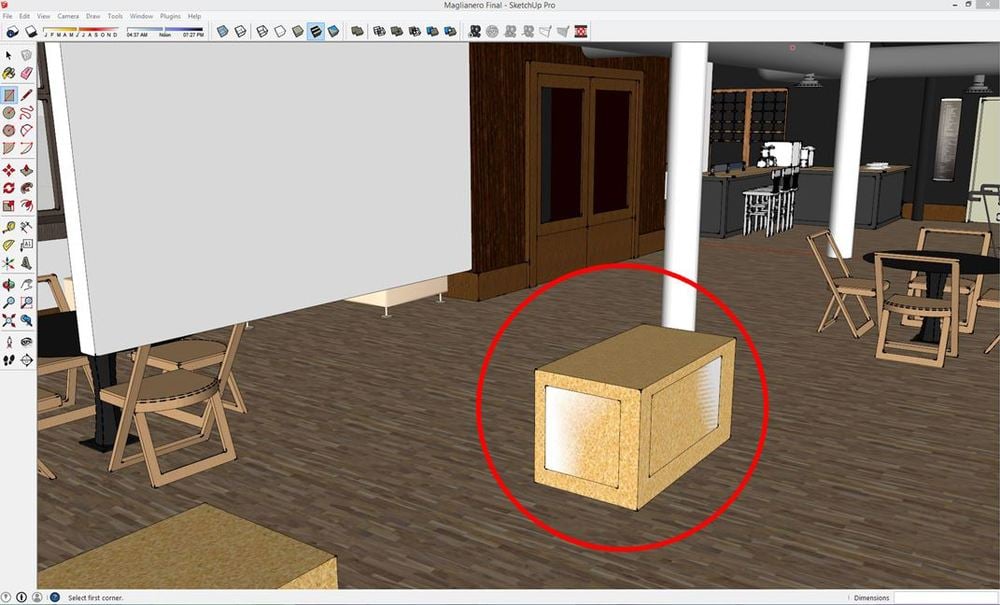

On the top floor of a beautifully renovated old mill building building in Cambridge, the mere mention of the term virtual reality conjures up images of devices more closely resembling Darth Vader’s helmet than a pair of ski goggles or sunglasses in the minds of most of the architects in the room. The skeptical faces of those around the conference table increasingly show gleams of intrigue as my colleague Shane plugs the Oculus Rift into his computer and pulls up a model in SketchUp or Revit. Without too much introduction, he shows off the model on the 2D screen and then invites someone to sit in the “driver’s seat.” Immediately after donning the pre-release virtual reality headset hardware, the first tester reaches out to touch one of the walls, points at a rafter, a skylight, and remarks about all of the interesting architectural features overhead. I love witnessing this reaction to the experience because it means that the user is fully immersed, walking through a specially realistic representation of the digital model that they just saw on screen. This is how most of our presentations go, to industry professionals and friends alike, at IrisVR. There is nothing quite like stepping out of reality and into a world that only existed in your mind or on a screen moments prior. One architect even stood up after trying a demonstration of the IrisVR beta software and placed his hand over his heart stating that he felt as though he had just walked into a building that he designed for the first time. In the case of this passionate architect and designer, the joy of experiencing his own creation made him feel “butterflies in his stomach.” I was quick to joke that virtual reality sometimes causes motion sickness, especially when using today’s early hardware models that have not yet been perfected. At the same time, the current technology is good enough to show the promise of virtual reality (VR) in the not-so-distant future.

.png?width=212&name=Prospect%20by%20IrisVR%20Black%20(1).png)